Why Simple Features Now Take Six Months

Why your architecture is the biggest financial risk you manage. And the 4 Phases of Strategic Debt.

If you walk into a room of engineers today and ask, “What is the purpose of software architecture?”, you will hear about scalability, modularity, defensibility, and clean code.

They are equally right and largely missing the point.

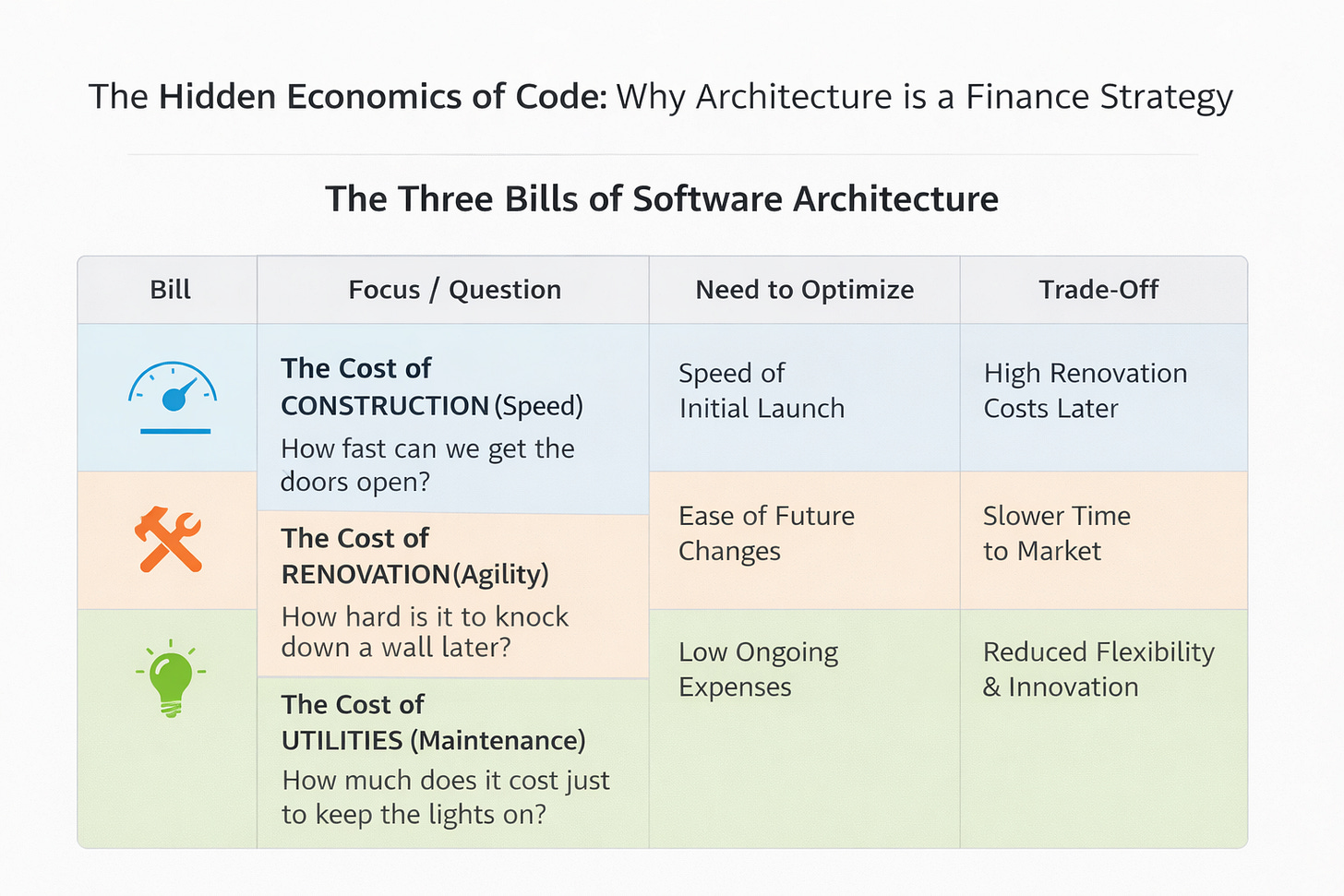

Architecture is not about art, and it is rarely about “perfection”. Architecture is a leverage mechanism whose only purpose is to give you control over the three bills you have to pay to keep a software organization alive.

At its root, every technical decision you make is simply a trade-off between three specific costs. You can minimize one, maybe two, but never all three.

The Three Bills You Must Pay

I like to think of a software product like a building project with three distinct financial pressures:

The Cost of CONSTRUCTION (Speed)

How fast can we get the doors open?

If you rush construction, you can open next week, but the wiring might be a mess behind the walls. You are borrowing speed from the future.

The Cost of RENOVATION (Agility)

How hard is it to knock down a wall later?

If you want a building that is easy to change later, you have to spend a fortune upfront on modular walls and flexible plumbing. You pay extra now to move fast later.

The Cost of UTILITIES (Maintenance)

How much does it cost just to keep the lights on?

Complex, custom buildings require expensive specialists to maintain. On the flip side, standardized buildings are boring, but cheap to run.

In what scenarios do you pay each bill?

Bad code is less of a common mistake plaguing most organizations. It’s more of paying the wrong bill at the wrong time. Owing to their respective sizes, a startup should not worry about renovation costs an enterprise should not worry about construction speed.

Below is a cheat sheet for how you can match your architecture based on your business stage.

Phase 0: Utility (Internal Tools)

In this scenario, you need a CRM for your sales team or a tracker for HR.

Your strategy is to NOT Build.

The logic is your goal is to pay zero construction costs and zero maintenance costs.

Your move is to use Notion. Use Excel. Do not write a single line of code. If you are building custom software for a solved problem, you are setting money on fire.

Phase 1: Hunting (Searching for Product-Market Fit)

In this scenario, you have a hypothesis, you have identified a critical problem with a growing / large surface area but no customers. You need to validate your idea before you run out of cash.

Your strategy is to be the “Dirty” Monolith. (This is a system where the architecture is intentionally suboptimal to achieve a critical business goal)

In this use-case, speed is the only metric that matters. Future “renovation” costs are irrelevant if the company dies next month.

Put everything in one big box (a Monolith). Hardcode the logic. Ignore “clean architecture.” If the product fails, you delete the code. If it succeeds, you can afford to fix it.

Phase 2: Scaling (You finally strike Gold)

Now, your customers love your product, and you are hiring 20 full-time engineers. As expected, all the “messy wiring” from Phase 1 is slowing you down.

Next, you need to deploy strategic decoupling

By that I mean, your biggest risk has shifted. It is no longer “will they buy it?”; it is “can we add features fast enough?” You must now invest in lowering the Cost of Renovation.

To achieve this, you can maintain the core messy system, and in parallel build new features as separate, clean modules (Microservices). You are now willing to pay a higher “utility bill” (managing complex servers) to buy back your agility.

Phase 3: Hypergrowth

You have 500 engineers and 20 Product Managers coordinating with them. Now, the biggest problem is teams stepping on each other’s toes.

You should be thinking phantomization at this point.

Remember, you are now paying down the debt from Phase 1. You need stability and independence.

Your focus is to invest heavily in “internal platforms.” You standardize everything. You now have to embrace high complexity as a feature, to ensure 50 teams can work in parallel without breaking the system.

In summary

Bad architecture is usually just good architecture applied at the wrong time.

Building a complex, flexible system for a startup is effectively suicide. You run out of money before you launch.

Running a billion-dollar enterprise on a “move fast and break things” monolith is negligence. In the long run, you will become too terrified to change anything.

Your job isn’t to pick the “best” technology. It is to know which cost you can afford to ignore today, and which one you need to optimize for tomorrow.

Fantastic framing of architecture as financial tradeoffs not technical perfection. The dirty monolith phase is where most startups mess up becuase they optimize for scalability they dunno they'll need instead of speed to validate. Worked at a startup that burned 6 months building a 'proper' microservices setup before launch and ran out of runway. The three bills metaphor cuts through so much engnineering ego.